Sarsaparilla

GENERAL

Sarsaparilla is a climbing plant, which belongs to the genus of climbing vines (Smilax). The plant can grow over 50 meters long, produces small flowers and, depending on the species, red, bluish or black berries, which are edible.

However, other plants with medicinal qualities are also called sarsaparilla, such as Hemidesmus indicus (Indian sarsaparilla) and Aralia nudicaulis (Wild sarsaparilla) which occurs in North America.

The genus Smilax consists of about 350 species, of which 79 species are found in China, 24 species are native to India, and 29 species are found in Central America. But they are also found, for example, in South America, Jamaica and the West Indies. However, these species are not only found there, but also in tropical, subtropical and temperate zones worldwide (see Salas-Coronado et al. 2017: 233).

Some sources group all Smilax species under the term "Sarsaparilla", while other sources refer only to species such as, for example, Smilax officinalis, Smilax japicanga, Smilax febrifuga, Smilax regelii, Smilax aristolochiaefolia, Smilax ornata, and Smilax glabra as Sarsaparilla [1] [2].

It is difficult to clarify the exact geographic and botanical origins of Sarsaparilla species, the following is a table of some different Sarsaparilla species and their synoyms (see Ahmad et al. 2019: 347):

The sarsaparilla root was and is used ethnomedically and was also an ingredient of the soft drink of the same name "Sarsaparilla" in the 19th century in the USA. Various studies showed that some species of the genus Smilax contain similar active ingredients and have similar effects (see Khan et al. 2019:4). For example, Smilax regelii was found to have a hepatoprotective effect, while an extract from the root of Smilax glabra appears to inhibit cancer cell growth, and extracts of Smilax larvata were found to have larvicidal and anti-fungal effects (Rafatullah et al. 1991; She et al. 2017; Hirota et al. 2015).

USE OF SARSAPARILLA WITH THE EXAMPLE OF SMILAX ORNATA

In folk medicine, 1-4 grams of sarsaparilla root is boiled and given 3 times a day for ailments such as chronic rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis, pain, inflammation and also as an additive to other treatments for, for example, rashes and psoriasis. The indigenous peoples of Central and South America used sarsaparilla as mentioned for rheumatism and skin rashes but also for impotence and as a tonic for physical weakness. Through the Spanish colonizers, sarsaparilla reached Europe from the New World, where physicians used it as a tonic, to purify the blood, as a diuretic, and to treat syphilis (see Khan et al. 2019: 4).

In Brazilian folk medicine, either an infusion or decoction of sarsaparilla (Smilax brasiliensis) roots is common. Here too, sarsaparilla is considered blood purifying, anti-rheumatic, diuretic, diaphoretic, etc. Furthermore, sarsaparilla is used there in combination with other herbs such as guaiac, sassafras, liquorice, and autumn daphne (see Soares et al. 2014: 75).

There are a number of sarsaparilla species, but the most interesting seems to be Smilax ornata (Jamaican sarsaparilla), whose root was used in the 19th century in the USA for the preparation of the then popular soft drink "sarsaparilla".

One study confirmed the anti-bacterial effect of Smilax ornata (see Ahmad et al. 2019: 350). Another study demonstrated an anti-inflammatory and analgesic effect of Smilax ornata root extract. In this study, the extract was also shown to have a comparable analgesic effect to ibuprofen. Among other things, it is suspected that Smilax ornata contains substances that could act at the opioid receptors (see Khan et al. 2019: 15). However, the substances responsible for the analgesic effect have not yet been isolated and the exact mechanism of action of these substances has not yet been investigated.

The phytochemical analysis of the root extract showed that alkaloids, tannins, saponins, steroids, glycosides, phenols and terpenoids are contained (see Khan et al. 2019: 14). There are no known side effects when taking a moderate dose, but too high a dosage can lead to nausea (see Winston et al. 2008: 390).

A LITTLE BIT OF SODA POP HISTORY

So-called soda fountains were common in the pharmacies and drug stores of the 1830s in the USA. They were an effective means of administering medicines by adding something for flavoring and some sparkling water, which enhanced the flavor of the medicines. Some soft drinks still known today were originally patented medicines, which in turn had their origins in folk medicine.

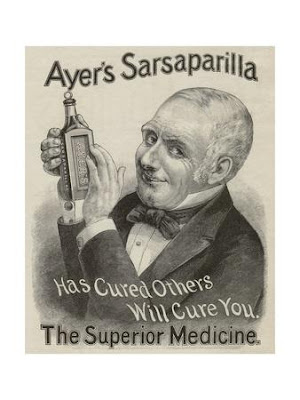

Very popular at that time were root beer, but also sarsaparilla. In 1824, a patent was filed for "Ayer's Sarsaparilla," which at the time was nothing more than a sweetened sarsaparilla drink and which was sold as a blood purifying medicine. In 1876, Charles E. Hires, a pharmacist, popularizes a bottled, effervescent herbal tea consisting of various herbs and roots. In 1880, he officially names his creation "Root Beer." In 1881, Imperial Inca Cola is invented, which is made from extracts of kola nut and coca leaves. About 4 years later, pharmacist Charles Alderton develops the formula of Dr. Pepper. In 1886, Dr. John S. Pemberton invents the formula for Coca-Cola, which at that time was still sold in pharmacies for headaches, among other things (see Schloss 2011: 8ff).

In Root Beer and Sarsaparilla, besides other roots and herbs, mostly 2 plants were found: namely Sassafras root and Sarsaparilla root. Sassafras used to be the main ingredient in many root beer recipes. Pharmacist Charles Hires was the first to present an effervescent tea made from roots and herbs in Philadelphia and later named this drink "Root Beer". Later, the positive effect of root beer on health was questioned. It was found that safrole, which is contained in sassafras root, seems to cause cancer in the liver. However, the market later quickly developed artificial flavorings to replace sassafras.

Kommentare

Kommentar veröffentlichen